Hirst explores the tensions and uncertainties at the core of human experience. Love, desire, belief and the struggle of living with the knowledge of death are all investigated, often in unconventional and unexpected ways.

Hirst is perhaps best known for his ‘Natural History’ series of works which present animals in vitrines suspended in formaldehyde. These iconic sculptures such as The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) or Mother and Child (Divided) (1993), aim to recast fundamental questions about the meaning of life and the fragility of biological existence.

Hirst uses the vitrines as both a window and barrier, seducing the viewer visually while also providing a minimalist geometry to frame, contain and objectify his subject. He first constructed a steel and glass tank in the seminal work A Thousand Years (1990), in which a miniature life cycle is created by flies hatching, feeding and then dying at the hands of an insect-O-cutor. In many of his other vitrine sculptures from the 1990s such as The Acquired Inability to Escape (1991) or The Asthmatic Escaped (1992), he implies a human presence through its absence, including relic-like objects such as clothes, cigarettes, ashtrays, tables and chairs.

Science and our unquestioning faith in the power of pharmaceuticals remains one of Hirst’s most enduring themes. These ideas are investigated in the installation Pharmacy (1992) as well as in the ‘Medicine Cabinets’ and ‘Instrument Cabinets’ which display a cornucopia of reflective, precision-tooled surgical implements within steel and glass cases. Other sculptures are more celebratory in tone such as Hymn (1999-2001), a polychrome bronze sculpture which reveals the musculature and internal organs of the human body as they are presented in toy-like anatomical models enlarged to a monumental scale.

In 2007 Hirst created what is arguably his most provocative work: For the Love of God, a life-sized platinum cast of a human skull, covered entirely by 8,601 VVS to flawless pavé set diamonds. Although without precedent in art history, the work operates as a traditional memento mori using an object to address the transience of human existence.

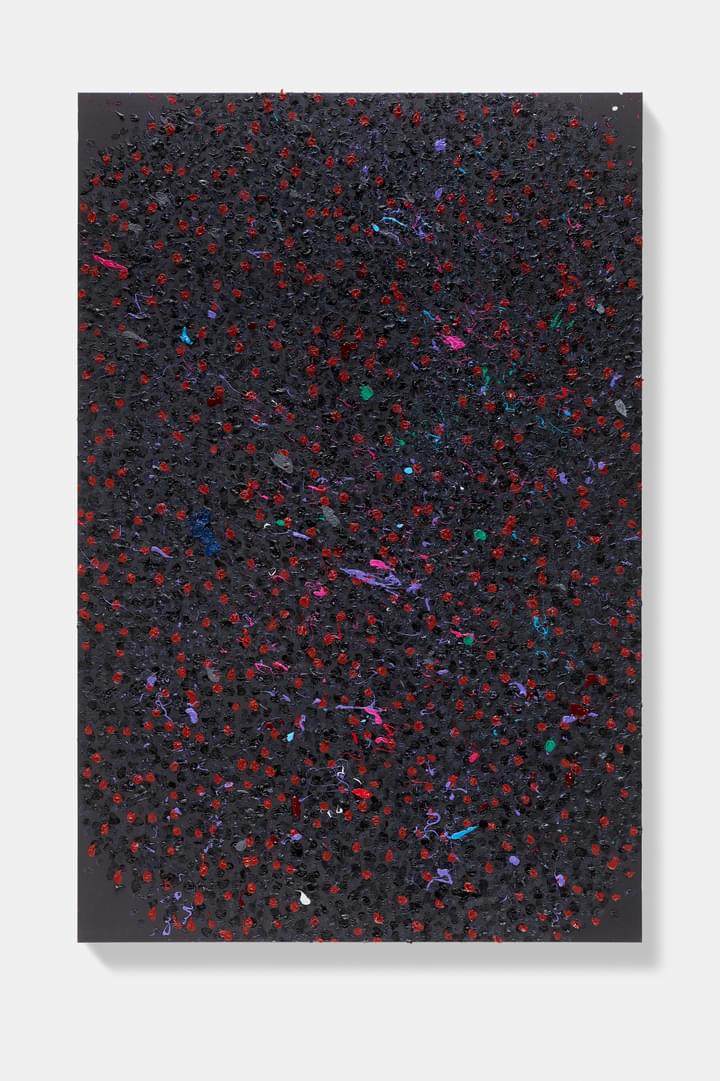

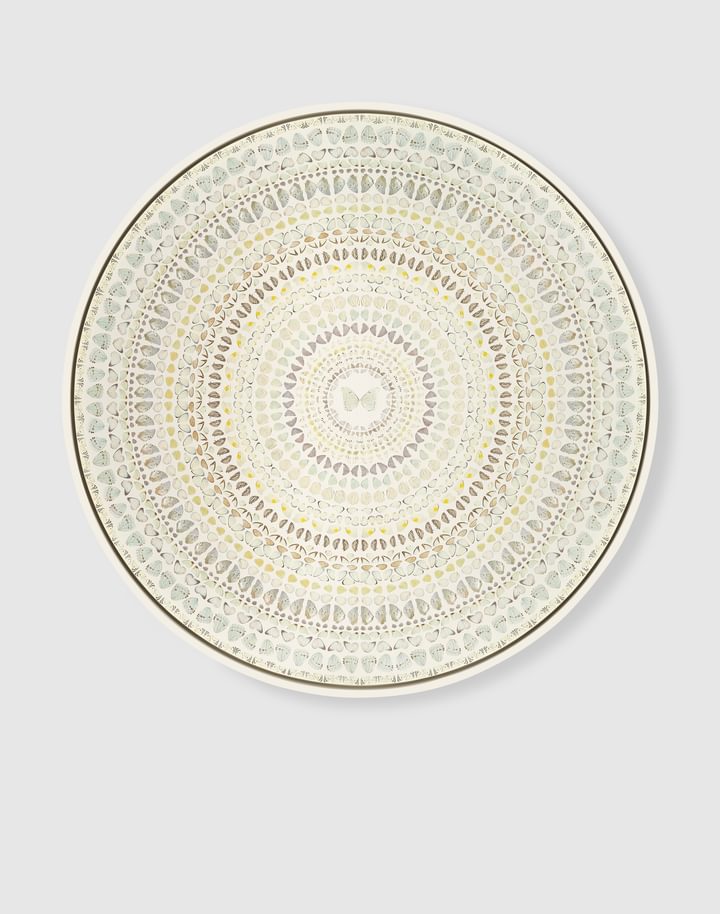

Hirst is equally well-known for his paintings such as the series of works with butterflies suspended in thick layers of gloss paint and the ‘Kaleidoscope Paintings’ where thousands of butterfly wings are arranged in mandala-like patterns. In the ‘Entomology’ paintings from 2013, he revisits this subject-matter again using butterflies interspersed with thousands of highly coloured insects and spiders to reflect the fragility of life. The corresponding ‘Entomology Cabinets’ utilise the same components but place them in precise horizontal or vertical rows inside minimal and reflective wall-mounted stainless steel frames. With each species arranged in separate rows, the overall effect is one of scientific ordering or industrial production, in part a reference to the Victorian era and it's predilection for visual displays that reflected man's control over nature.

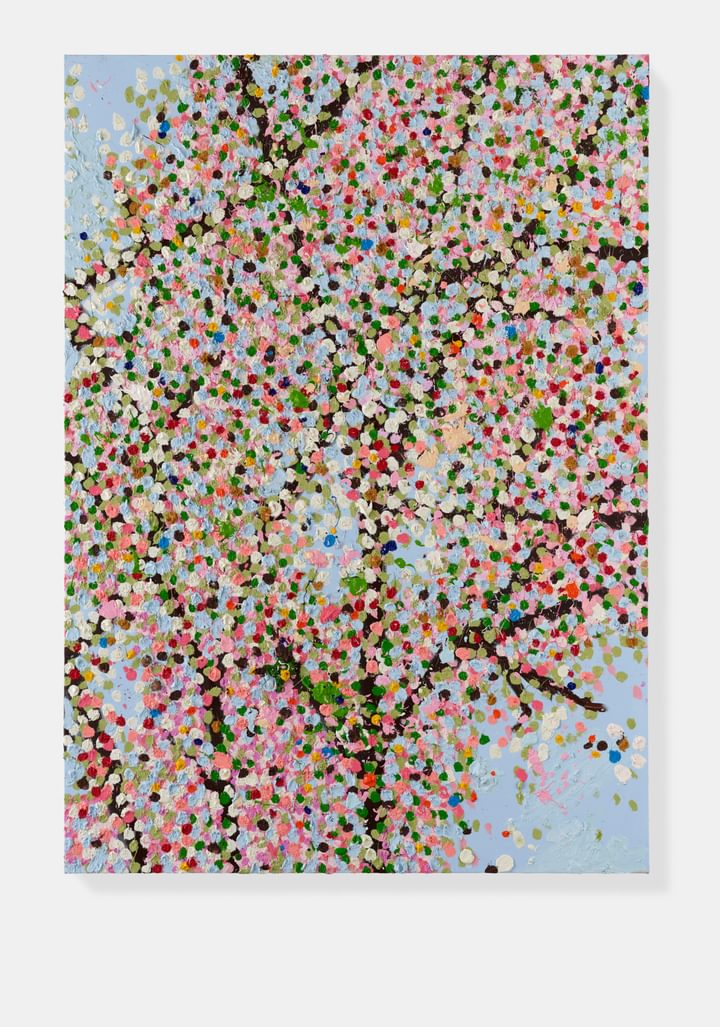

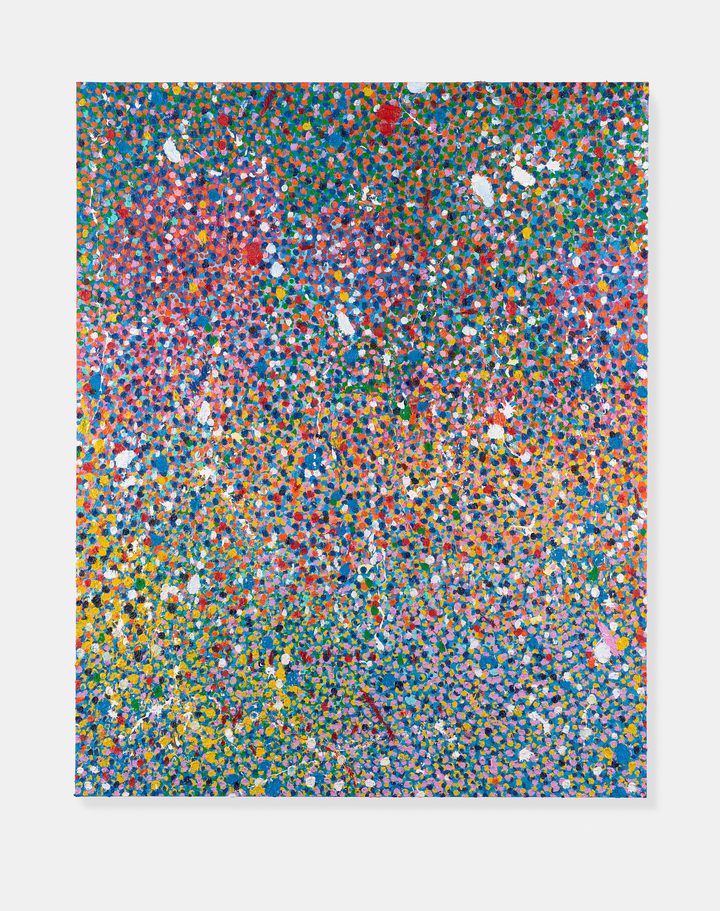

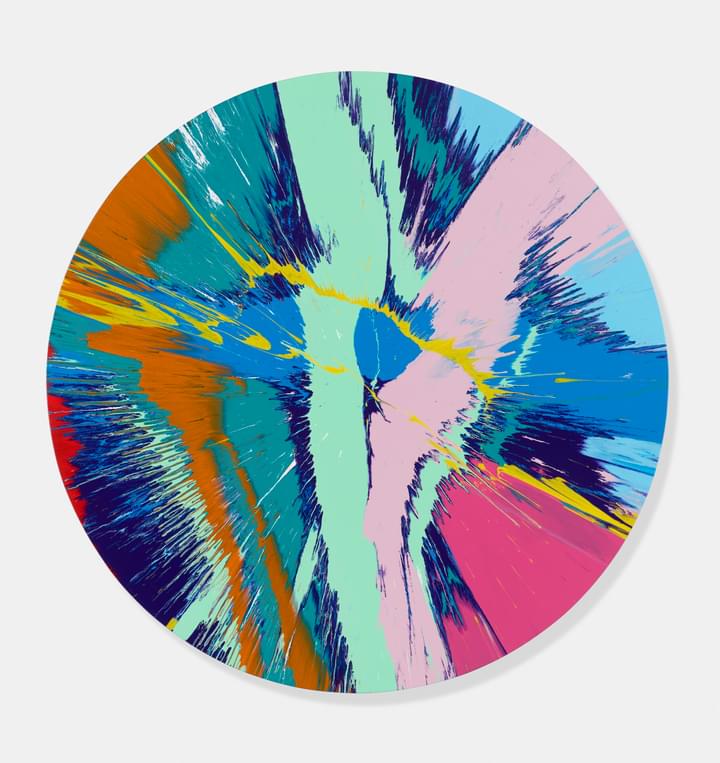

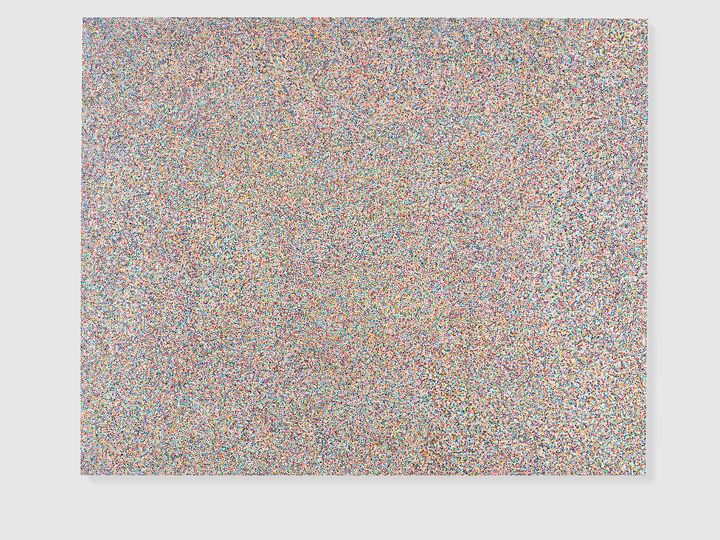

In the ‘Spin’ series, Hirst uses a machine that centrifugally disperses the paint as it is steadily poured onto the canvas. The chance spontaneity of the ‘Spins’ stands in contrast to the more formulaic ‘Spot’ series which have a rigorous grid of uniformly sized dots in different colours. Both series, however, suggest the idea of an imaginary mechanical painter. Contrastingly, in 2009 Hirst embarked on a series of paintings that represented a radical shift, returning to painting alone, what he has described as the ‘most direct form of production, with all the attendant artistic consequences: facing the canvas, the individual painterly act, the creative process, the artist’s emotional balance – alone; being at the mercy of issues raised by the picture, at the mercy of the creator, of oneself…’

In 2017, Hirst presented his ten-year long project Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable at Punta Della Dogana and Palazzo Grassi in Venice. Examining notions of collecting and the mechanisms of art history, as well as human endeavour in the face of mortality, the project is manifested through almost 190 separate works. These focus on a series of treasures and artefacts collected by the freed Roman slave Cif Amotan II, hauled from a ship wreck in the Indian Ocean which had lain untouched for 2,000 years. Weaving fact and fiction to create a labyrinthine narrative, Hirst combines valuable archaeological relics hauled from the wreck – some of which are so encrusted with coral and marine life that their forms are unrecognisable – with his own sculptures, documentary photography, video and drawing. The project highlights the power of myth, told through a hierarchy of objects that range from coins and plates to monumental sculptures, to expose ideas of value and the mutability of history, belief and art itself.

Damien Hirst was born in 1965 in Bristol, UK. He lives and works in London and Gloucestershire. Since 1987, over 90 solo Damien Hirst exhibitions have taken place worldwide, and he has been included in over 300 group shows. In 2012, Tate Modern, London presented a major retrospective survey of Hirst’s work in conjunction with the 2012 Cultural Olympiad. Hirst’s other solo exhibitions include Qatar Museums Authority, ALRIWAQ Doha (2013–2014); Palazzo Vecchio, Florence (2010); Oceanographic Museum, Monaco (2010); Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (2008); Astrup Fearnley Museet für Moderne Kunst, Oslo (2005); Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples (2004); Palazzo Grassi and Punta della Dogana, Pinault Collection, Venice (2017), Post Truth, Fake News & Alternative Facts, Haifa Museum, Israel (2019), Villa Borghese, Rome (2021); Fondation Cartier, Paris (2021) amongst others.

His work features in major collections including the British Museum, The Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Tate, the Stedelijk Museum, the Yale Center for British Art, The Broad Collection, the Victoria and Albert Museum, Fondazione Prada, and Museo Jumex, among many others.