Following a degree in archaeology, anthropology and art history, Gormley travelled east and spent a year getting to and then two years in India before returning to London to study art, graduating first from Goldsmiths and then from the Slade School of Fine Art in 1979. In India, he discovered Vipassana meditation, an experience which he later credited as the singular most important of his life. Interior reflection and the creative potential associated with a meditative state of mental and physical stillness continue to deeply inform his work.

Immediately following his return from India, Gormley laid plaster-soaked sheets over the bodies of friends to make hollow shells that delineate a shrouded human form. ‘I was touched by the repeated sight all over India of people asleep covered by thin cotton saris or dhotis in the streets and on railway platforms’, Gormley explains, and he considers one such sculpture, Sleeping Place (1974), his first ‘serious work’. At art school, he then sought a more direct relationship to material to explore how, for example, the surface of a stone carries the story of its own making, or the exposed annular rings of a tree make time visible. Gormley transferred these thoughts to materials closer to human life, like bread that sustains us, as in Bread Line (1979) and Bed (1980–81), and clothes that shelter us, as in My Clothes (1980): ‘Those sculptures led me to realise that I had no choice but to use my existence as the basis of my work and my own body as material, subject and tool.’

Influenced by Joseph Beuys’s expansive notion of art as a transformative social process, Gormley began to use his own body as an immediate ‘life reference’, treating it as a found object exemplary of a collective condition. In the 1980s onwards, he started to mould his own body in plaster for sculptures that effected what he terms ‘an embodied moment of human time captured in matter’. The intimate and often uncomfortable moulding process required the artist to be completely still so that he could be tightly wrapped in cling film and plaster-soaked scrim. This was done in close collaboration with his partner, the artist Vicken Parsons, who would first apply the scrim and then release Gormley once the plaster had hardened by sawing it open. The mould was then strengthened with fibreglass, around which the artist beat sheets of lead, joining them along strict vertical and horizontal axes. The first work made using this process, Three Ways: Mould Hole and Passage (1981–82), is the artist’s proposition that the body is a place as well as a site of potential transformation. Here, the body, treated as a whole system, is not used for individual expression, but calls on the viewer’s subjective experience to make objects that are reflexive rather than representational.

In the 1990s, these hollow body-cases became solid, transforming the space of the body into mass to effect a complete displacement of space itself. Around this time, Gormley produced his now iconic series of cast iron body-forms, including the major installation Critical Mass II (1995) in which 60 body-forms articulate 12 different physical states. Industrially made, Gormley considers these bodies ‘fossils’ and ‘mineral masses’ that record lived moments in time. First installed in a disused tram station in Vienna as an anti-monument to victims of the 20th century, Critical Mass II was subsequently installed in the courtyard of London’s Royal Academy of Arts, where the presence of its multiple prone, upturned or suspended figures implied profound questions about the progress of intellectual enlightenment. It has since been seen in different formations and a variety of contexts, from the Forte di Belvedere in Florence to the Musée Rodin in Paris.

Inhabiting a long narrative of sculpture, running from prehistory to the present day, the notion of an indexical body print, a human trace or an echo resonates throughout Gormley’s practice. While the early lead works were formed over moulds cast from the artist’s body, requiring long periods of stillness, later sculptures stem from digital scanning, which allows the artist to hold poses that are more difficult or dynamic: twisting, balancing, leaning and even holding other sculptures. This coincided with the artist’s move towards the language of architecture, making works that reconcile what Gormley sees as the ‘first body’, our biological body, with the ‘second body’ of our built environment.

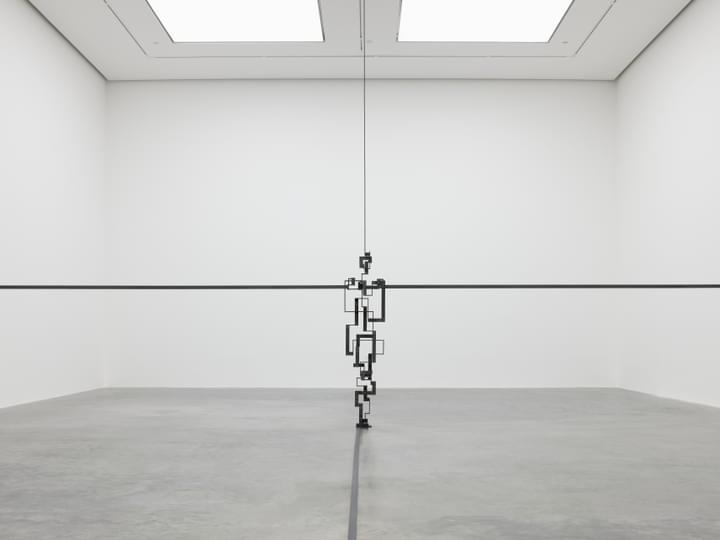

The notion of the body as building runs through Gormley’s sculpture, particularly those composed of aggregated blocks or open metal space frames that define the spatial volumes of the body. The artist’s ongoing ‘Blockworks’ series, begun in the early 2000s, initiated this investigation into the relationship between the body and architecture by replacing anatomy with architectonic volumes and using stacking, cantilevering and balance to achieve a stable structure that is still dynamic. Increasingly, the blocks have become larger and more austere, often extending beyond the skin in an attempt to evoke particular feelings and tensions. Other works, such as the ‘Proppers’, employ the tectonics of architecture to translate body mass into the equivalent of a high-rise tower. These concerns are also reflected in many of his large-scale projects such as Model (2012), in which 100 tons of steel articulate the body as an enterable building, or Alert (2022), a squatting, precariously balanced body built from cantilevered slabs of weathering steel.

Considering the body as both a construction and dwelling place, and of sculpture as a way of thinking through material, the body in Gormley’s sculptures rejects individuality, instead foregrounding the infinite space at the core of being. ‘My subject is not about identity or psychology. It’s about trying to accept the potential of inner extension. It’s a paradox that our body is a physical thing, an object in the world, but that it also contains consciousness that has this potential of infinite expansion’, he has remarked.

Constantly searching for new ways to evoke human experience led Gormley to dematerialise or disarticulate the body’s anatomical totality into various aggregate or organic structures, from the Weaire-Phelan bubble matrix to the Cartesian coordinates to crystal stereometry. The ‘Drift Works’, for example, employ stainless steel bar in dense, cloud-like suspensions that articulate a body free-falling through space, the ‘Polyhedra Works’ reconcile the body with crystalline systems of mineral aggregation found in rock and the ‘Expansion Works’ renegotiate the body’s boundary by pushing beyond the limits of the skin to create large organic forms that recall single-celled organisms, fruits or vegetables. In recent years, Gormley’s work has become increasingly fluid and open, tending towards loops that map body-space, as in his ‘Strapworks’, sometimes breaking free of the skin’s bounding condition to question where the body begins and ends.

For Gormley the exhibition is always a testing ground, the visitor the true subject of his work. Key to its effect is its active relationship to surrounding space and a heightened articulation of the viewer’s physical encounter with the widest possibilities of sculpture. Since Room (1980), an enclosure the size of a standard room made from unpeeled layers of clothing, he has sought to make proprioceptive environments that challenge and catalyse the space-time experience of the viewer. Feeling Material XIII (2004), for example, spirals a steel line out from a body zone towards its surrounding environment, entangling visitors in a seemingly unending web of energy. This line then becomes entirely abstract in Clearing I (2004) and Turn (2023), three-dimensional, high-energy ‘drawings’, in aluminium and bamboo respectively, through which visitors are encouraged to duck and dive. This investigation into environments that foreground the bodily experience of the viewer over the materialisation of a singular body continues in installations such as Breathing Room I (2006) and Blind Light (2007), the latter described by the artist as a space in which ‘you become the subject of the work, a figure immersed in an endless ground’. This ambition returns in one of Gormley’s most radical sculptural propositions, Horizon Field Hamburg (2012), a suspended platform floating nearly eight metres off the ground. This vast, black, reflective surface offers a participatory space where visitors can reconnect with walking, feeling, hearing and seeing – a literal sounding board for their own subjective experiences. Human interaction also animates Lost Horizon II (2017) and Matrix III (2019), the former a forest of bungee cords that both resists and remembers a body’s journey through its taut, vibrating field of vertical ropes, and the latter an expansive, hovering, axial cloud that confounds the eye, producing a reversed sense of vertigo.

Some of Gormley’s most well-known works inhabit public space and become part of the activity of daily life. The permanent installation Another Place (1997) features 100 cast iron body-forms sited above and below the tide line at Crosby Beach in Merseyside, facing outwards towards the sea. Perhaps his most famous work, Angel of the North (1998), near Gateshead, is a monumental steel sculpture rising 20 metres above the ground and spanning 54 metres wide, the result of five years of collaboration using historic industrial methods inspired by the region’s history of shipbuilding. Situated adjacent to the major A1 motorway on the site of a former colliery, it has become a national landmark, a celebration of collectivity that invokes the great industrial traditions of the UK and a beacon of hope for the future. Collective labour also underpins Gormley’s series of ‘Field’ installations that consist of a multitude of hand-sized clay figures amassed to occupy an entire room. A collaborative project produced with different communities on four continents, the largest is Asian Field (2003) numbering approximately 210,000 figures made with 350 people of all ages in the village of Xiangshan, north-east of Guangzhou, China.

A daily activity for the artist, drawing provides a ‘laboratory’ for this exploration, a seedbed or fertile ground in which ideas for sculpture might evolve. Gormley’s drawings are executed with many different media, including carbon, casein, chicory, walnut ink, blood and linseed oil, and their transformation as they are combined on paper is evocative of different biological and geological processes. While the solitary practice of drawing forms a counterpoint to his sculpture, which is collective in approach, both are grounded in physical form and a deep relationship to materiality, space and scale. For Gormley, ‘a day without drawing is a day lost.’

Gormley’s work has been widely exhibited throughout the UK and internationally with exhibitions at Musée Rodin, Paris (2023); Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany (2022); Museum Voorlinden, Wassenaar, Netherlands (2022); National Gallery Singapore, Singapore (2021); Schauwerk Sindelfingen, Germany (2021); Royal Academy of Arts, London (2019), Delos, Greece (2019); Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy (2019); Philadelphia Museum of Art, Pennsylvania (2019); Long Museum, Shanghai (2017); Forte di Belvedere, Florence, Italy (2015); Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland (2014); Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasilia (2012); Deichtorhallen, Hamburg, Germany (2012); The State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia (2011); Kunsthaus Bregenz, Austria (2010); Hayward Gallery, London (2007); Malmö Konsthall, Sweden (1993); and Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark (1989). Permanent public works include the Angel of the North (Gateshead, UK), Another Place (Crosby Beach, UK), Inside Australia (Lake Ballard, Western Australia), Exposure (Lelystad, Netherlands) and Chord (MIT – Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts).

Gormley was awarded the Turner Prize in 1994, the South Bank Prize for Visual Art in 1999, the Bernhard Heiliger Award for Sculpture in 2007, the Obayashi Prize in 2012 and the Praemium Imperiale in 2013. In 1997 he was made an Officer of the British Empire (OBE) and was made a knight in the New Year’s Honours list in 2014. He is an Honorary Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects, an Honorary Doctor of the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of Trinity and Jesus Colleges, Cambridge. Gormley has been a Royal Academician since 2003.